Every now and then you find fortune in the humble wool of a sheep's back. Such is the case here, when, at a recent purchase of a large group of rugs we came across some fairly rare Tibetan rugs.

Now modern Tibetan rugs are not at all rare these days, and they pretty much corner the market when it comes to high-quality contemporary designs. But here is the thing. First of all the modern "Tibetan" rug market is actually a Nepalese rug market. Rugs designated as "Tibetan" today are in fact made by Tibetans who had to flee from Tibet to Nepal due to Chinese expansionism. Tibetan wool is of a high grade. The knot is the classic Tibetan knot, that seems to be tattooed on the neck or shoulder of every second young woman these days. So the long and the short of it is that although there are many modern "Tibetan" rugs, there are not many real antique Tibetan rugs out there.

A few blogs ago I focussed on Tibetan tiger rugs. In the course of that blog I outlined how exceedingly rare these Tibetan rugs are. There are reports that there are only a few hundred "old" Tiger rugs out there - meaning from the early 1800s. I also mentioned how it was only in relatively recent times that the very first Tibetan rug was smuggled/purchased and brought out of Tibet, to find a new home in the Smithsonian. So was the first incursion made by Western curiosity into the material culture of Tibet, a name that conjures up a rosy tint in the imagination of most westerners. Here is a photo of this much spoken of particular rug...Observe the motifs, particularly the roses and T border - these come into the discussion later.

|

| Top saddle rug. The famous first Tibetan rug to appear in the west, now in the Smithsonian. |

The same geography that has kept this region so remote also has contributed to so much Tibetan rug production being undertaken in this region. Much of Tibet is arid. But the waters flowing off the mountains into major and secondary river valleys are bountiful and the land is good for pastoral activities. The wool is soft and high quality. So this area was an epi-center of Tibetan rug production.

And on a final geographic note, it is important to realise that this part of the Himalayas was the entrypoint for expensive indigo from India.

Before we look at our pieces, it should quickly be said that Tibetan rug-making has generally fallen outside of the more detailed histories of Persian and Turkish schools. The knot is different and generally low-knot counts were used, even as low as 15 knots per, inch, which is about as low as you can go. Some Persian Isfahan carpets, by comparison, were made using closer to 800 knots per square inch.

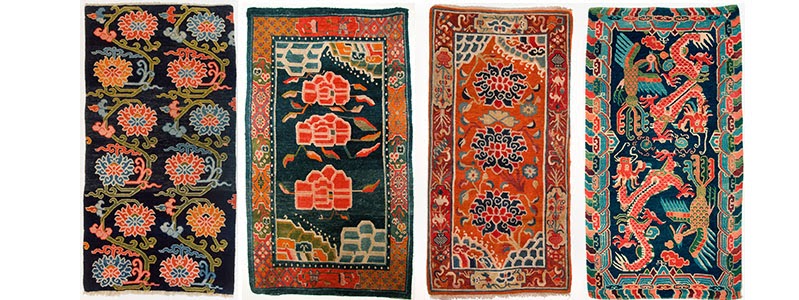

The Tibetans also made textiles more in keeping with their own cultural requirments, lots of fittings and trappings for transport, ornamental throne seats, and most importantly in this particular case, the khaden, or sleeping mat, of which we have four show here, along with one saddlebag. These sleeping mats are exceedingly rare. But in this lot we discovered four - lets take a look at them.

The Group. Four Khaden rugs and one saddlebag.

So, what do you think? Colorful, aren't they? Very pretty stuff. And if they are old and rare, very pretty and expensive stuff. Now here are the four pieces in detail, placed in what I think is the chronological order. I will explain my reasons below.

Khaden #1

Khaden #2

Yes indeed, very pretty! But what age? What value? One would think that there had been 100 books written on Tibetan rugs but that is not the case. There is very little literature on the subject. The problem is that even in this day and age when we can go to the moon we still don't know much about these old Tibetan pieces from the Nyang River Valley.

It is well worth recalling that the predatory powers of Britain and Russia didn't really manage to mount any real expedition into Tibet until close to 1900 - not to say that this was not familiar terrain for the spies of "The Great Game".

Here is a rare photo from the 1890s showing a Tibetan priest seated on a Tiger Rug. As was discussed in my blog on tiger rugs the tiger motif was meant to possess protective powers. I show this picture because the tiger rug is of the abstract tiger stripe school, divided into two halves, with a pearl border and the stupa-rose. Now go to the first image at the top of this blog. You are already familiar with the tiger rugs. But compare this particular rug to the one at the top of this blog, the one housed in the Smithsonian. Compare the stupa-roses, which are identical, as well as the pearl border. What this tells us is that we are dealing with the same carpet tradition here. Not only tiger rugs but also these more elaborate Tibetan pieces probably, at least stylistically, came from the same source.

So let's look at some genuine old Khaden rugs from the early 1800s. They can easily be sorted into groups based on design. The first group, shown below, has three medallions, stupa-roses, pearl inner borders and interlocking T outer borders.

Here is a second group of old pieces. Again, three madallions is the norm, but this time with a pearl inner border and a running swastika outer border.

Discussion. So what can we make out of our own rugs?

First, we know that the four khaden we possess are far more colorful than anything classified as a genuine antique. The orange in the fourth khaden looks suspiciously artificial, although natural sources of orange were relatively available. However, the blue in the first khaden looks like real indigo.

Design-wise there are also very noticeable differences. There are no pearl borders, no T borders, no swastika borders. The three medallion pattern is still adhered too but the first khaden, the indigo khaden, has an all-over pattern that is not seen in the really old antiques.

Of course, as rug collectors, this is not necessarily the news you want to hear. You want to be told that you have rugs that should be in the Smithsonian, sell them and retire. But that is not about to happen and here is why...

Look at this sample of khaden from the early 1900s. Stylistically, our Khaden #1 has much more in common with the left-most piece, which also lacks any border. And the orange in the our Khaden #4 has a lot in common with the third piece depicted here. Perhaps most important is the adoption of Chinese elements in the design, seen most prominently in the "rainbow border", the multi-colored stripes, of the fourth rug, but also in two of our own pieces.

The "China-fication" of khaden at this time should come as no mystery. Throughout the 1800s the Turks of Central Asia and the Chinese had been fighting it out for control of what was traditionally known as Eastern Turkestan. This is the region to the east of the Pamirs, which drops down into the Tarim Basin, and, further south, the Tibetan Plateau. Up until around 1900 the Turks maintained the upper hand in this region, and the Tibetan rug styles could be argued to find their origins in this Turkish influence.

But then the Chinese got the upper hand, and, after Mao, really cemented the Chinese position, incorporating this area into Xinjiang Province ("The New Province"). If you have been following the news you will have seen in the past year many clashes between the indigenous Turkish Uyghurs and the Chinese who have been migrating west to this new province, in the process stamping out any Turkic exoticism in favour of a Sovietski concrete blocks. It is a disgusting and unforgiveable shame. Silk Road wonders such as Kashgar, Yarkhand and Khotan are being stripped of all that was once mysterous and wonderful, in favour of the cold and clinical decisions made by bureaucrats in Beijing. The taking of Tibet is a land-grab of enormous proportions, that, if it had happened in Europe, would have led to certain war. Alas, for the poor Tibetans.

Of course, all of this is closely tied up with dating the rugs. With Mao there was a general exodus of Tibetans, led by the Dalai Lama, from Tibet into Nepal and India. I think we can safely assume that these khaden were baggage in this exodus, before ultimately ending up in the western market.

But if there are Chinese motifs in increasing numbers after 1900 then one must presume that the Tibetan rug makers were catering to Chinese needs. This must also predate the Tibetan exodus, for no Tibetan worth his salt would make a Chinese style Tibetan rug.

So my guess is this. These khaden were probably made sometime between 1890 and 1940. They are a combination of vegetable and artificial dyes. Khaden of this vintage are selling, rarely, at auction in the vicinity of $3000 each.

But I think these are grossly underestimately values. The reason being that we are dealing with a very limited pool of pieces made in a small area over a short period. These types of rugs are still largely unknown. Once there is a more widespread appeciation for the rarity of these Tibetan khaden, their value is sure to sky-rocket.

The Group. Four Khaden rugs and one saddlebag.

|

So, what do you think? Colorful, aren't they? Very pretty stuff. And if they are old and rare, very pretty and expensive stuff. Now here are the four pieces in detail, placed in what I think is the chronological order. I will explain my reasons below.

Khaden #1

Khaden #3

Khaden #4

Yes indeed, very pretty! But what age? What value? One would think that there had been 100 books written on Tibetan rugs but that is not the case. There is very little literature on the subject. The problem is that even in this day and age when we can go to the moon we still don't know much about these old Tibetan pieces from the Nyang River Valley.

It is well worth recalling that the predatory powers of Britain and Russia didn't really manage to mount any real expedition into Tibet until close to 1900 - not to say that this was not familiar terrain for the spies of "The Great Game".

Here is a rare photo from the 1890s showing a Tibetan priest seated on a Tiger Rug. As was discussed in my blog on tiger rugs the tiger motif was meant to possess protective powers. I show this picture because the tiger rug is of the abstract tiger stripe school, divided into two halves, with a pearl border and the stupa-rose. Now go to the first image at the top of this blog. You are already familiar with the tiger rugs. But compare this particular rug to the one at the top of this blog, the one housed in the Smithsonian. Compare the stupa-roses, which are identical, as well as the pearl border. What this tells us is that we are dealing with the same carpet tradition here. Not only tiger rugs but also these more elaborate Tibetan pieces probably, at least stylistically, came from the same source.

|

| Tiger rug beneath priest table. Alongside matching Khamdrum rug.1880s. |

|

| Stylised Tibetan tiger rug, showing border elements typical of the Nyang River. |

|

| Khaden, sitting and sleeping rugs, with interlocking T border. Early 19th century AD. |

|

| More khaden rugs with interlocking swastika motif. |

First, we know that the four khaden we possess are far more colorful than anything classified as a genuine antique. The orange in the fourth khaden looks suspiciously artificial, although natural sources of orange were relatively available. However, the blue in the first khaden looks like real indigo.

Design-wise there are also very noticeable differences. There are no pearl borders, no T borders, no swastika borders. The three medallion pattern is still adhered too but the first khaden, the indigo khaden, has an all-over pattern that is not seen in the really old antiques.

Of course, as rug collectors, this is not necessarily the news you want to hear. You want to be told that you have rugs that should be in the Smithsonian, sell them and retire. But that is not about to happen and here is why...

|

| Khaden of the early 1900s. |

Look at this sample of khaden from the early 1900s. Stylistically, our Khaden #1 has much more in common with the left-most piece, which also lacks any border. And the orange in the our Khaden #4 has a lot in common with the third piece depicted here. Perhaps most important is the adoption of Chinese elements in the design, seen most prominently in the "rainbow border", the multi-colored stripes, of the fourth rug, but also in two of our own pieces.

The "China-fication" of khaden at this time should come as no mystery. Throughout the 1800s the Turks of Central Asia and the Chinese had been fighting it out for control of what was traditionally known as Eastern Turkestan. This is the region to the east of the Pamirs, which drops down into the Tarim Basin, and, further south, the Tibetan Plateau. Up until around 1900 the Turks maintained the upper hand in this region, and the Tibetan rug styles could be argued to find their origins in this Turkish influence.

But then the Chinese got the upper hand, and, after Mao, really cemented the Chinese position, incorporating this area into Xinjiang Province ("The New Province"). If you have been following the news you will have seen in the past year many clashes between the indigenous Turkish Uyghurs and the Chinese who have been migrating west to this new province, in the process stamping out any Turkic exoticism in favour of a Sovietski concrete blocks. It is a disgusting and unforgiveable shame. Silk Road wonders such as Kashgar, Yarkhand and Khotan are being stripped of all that was once mysterous and wonderful, in favour of the cold and clinical decisions made by bureaucrats in Beijing. The taking of Tibet is a land-grab of enormous proportions, that, if it had happened in Europe, would have led to certain war. Alas, for the poor Tibetans.

Of course, all of this is closely tied up with dating the rugs. With Mao there was a general exodus of Tibetans, led by the Dalai Lama, from Tibet into Nepal and India. I think we can safely assume that these khaden were baggage in this exodus, before ultimately ending up in the western market.

But if there are Chinese motifs in increasing numbers after 1900 then one must presume that the Tibetan rug makers were catering to Chinese needs. This must also predate the Tibetan exodus, for no Tibetan worth his salt would make a Chinese style Tibetan rug.

So my guess is this. These khaden were probably made sometime between 1890 and 1940. They are a combination of vegetable and artificial dyes. Khaden of this vintage are selling, rarely, at auction in the vicinity of $3000 each.

But I think these are grossly underestimately values. The reason being that we are dealing with a very limited pool of pieces made in a small area over a short period. These types of rugs are still largely unknown. Once there is a more widespread appeciation for the rarity of these Tibetan khaden, their value is sure to sky-rocket.

.svg.png)